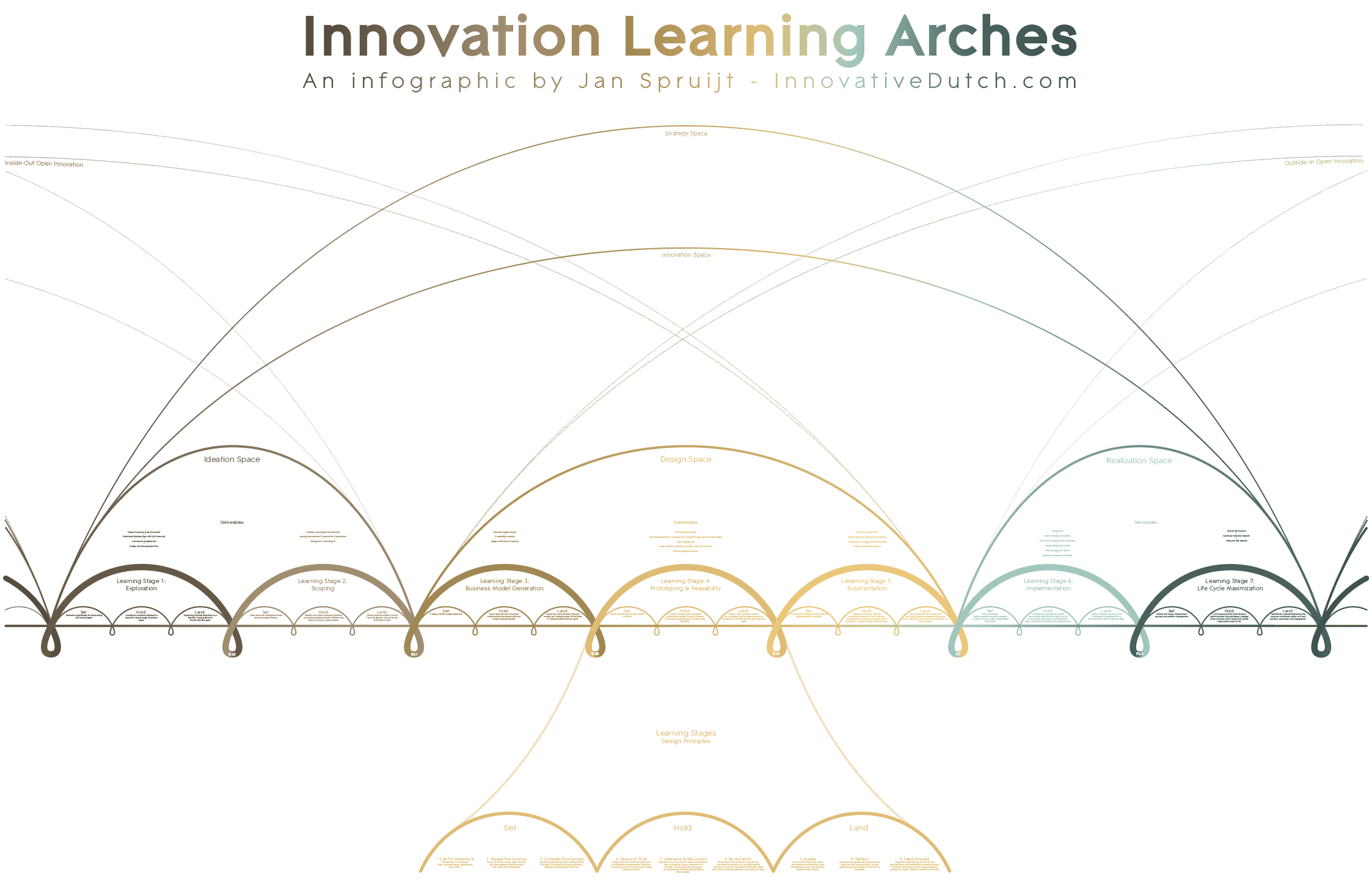

What if we look at innovation from the perspective of learning? In that case, the sole intention of innovation management is not systematically generating and implementing viable offerings, but optimizing the amount of learning that an organization can handle when dealing with processes of creativity. For the purpose of this infographic I’ve combined the theories on a) stage-gate processes in innovation and technology development, b) organization learning and absorptive capacity and c) learning arches as they are widely used on higher education.

This infographic is part of the book Innographics: A Visual Guide to Innovation Management

Download a 32-page preview for free

Including 2 infographics, 2 chapters and an overview of 28 innographics.

☑ I agree with opting in for the newsletter, our terms and privacy policy.

Stage-Gate Processes

Due to its complexity, business innovation is still not fully understood and is an ongoing topic of research. Van De Vrande (2017) mentioned three trends that are inextricably linked to the increasing demand for professionalization of innovation processes in organizations. Organizations need to: – continuously invest in the exploration of new business and innovation – and develop agile business models in response; – adopt new (digital) technology at an early stage, combine it with existing capabilities and adjust their business model towards it; – open up to exchanging (new) knowledge and co-create new business models with others. She argued that these trends directly result from the fourth industrial revolution and cause unpredictability and uncertainty for organizations. Start-ups and large companies both benefit from having a process view towards innovation in place. An excellent article from 2011 by Gerry Katz provides an overview of the different models that have been developed around innovation processes and New Product Development. In short:

- — 1980: New Product and Development Service Process (Hauser)

- – 1986: Stage Gate (Cooper)

- – 1992: Innovation Funnel (Wheelwright & Clark)

- – 1992: New Product Development Funnel (McGrath)

- – 2005: Innovation Funnel (MIT)

Cooper’s model for Stage-Gate Innovation is widely accepted in industry. In the work I’ve done, I’ve come across dozen of different lay-outs of the Stage-Gate Funnel. Some of them existing of only 3 stages, other of 11 stages. Some of them focusing on pre-stage innovation much more than others. Some of them including several post-introduction stages as well. From what I’ve seen, I concluded there are 7 very common stages and their accompanying gates:

- Exploration

- Scoping

- Business Model Generation

- Prototyping & Feasibility

- Substantiation

- Implementation

- Life Cycle Maximization

Crossan & Apaydin (2010) cross-checked 13,995 academic papers that were published over 27 years to derive general topics that belong to an innovation strategy. Their overview makes a distinction between ‘determinants of innovation’ (i.e. the innovation processes, methodologies and procedures that companies build to structure innovation) and the ‘dimensions of innovation’ (i.e. the managerial levers of innovation that enable the processes, such as leadership, culture and business models). In line with that, and following the reasoning of McKinsey’s model of the three horizons (Coley, 2009), DaSilva and Trkman (2014) argued that companies need to create an ‘innovation strategy’ for the long-term, develop ‘dynamic capabilities’ for the mid-term and be able to exploit a business model in the short-term. The latter asks for a stronger approach towards organization learning in innovation processes.

Organizational Learning

The degree of unpredictability of the market asks for the creation of new business models. This process-based approach to business models is called ‘Business’ Model Innovation” (Leih, Linden, & Teece, 2015). Unlike commonly used innovation methodologies such as the innovation funnel and the stage-gate model (Cooper, 1990; Cooper & Edgett, 2009) this process-based approach to the innovation of business models is a result of design-oriented thinking – ‘design thinking’ – in management science (Romme & Endenburg, 2006). Nobel Prize winner Simon argues that in the complexity of innovation, the creation and sharing of explicit knowledge is hindered by ‘human intentionality’ and ‘environmental contingency’. Therefore, the development of knowledge in the management domain calls for two continuous coherent approaches of ‘discovering’ and ‘validating’ (Simon, 1969/1996). Simon argues that this form of ‘bounded rationality’ necessarily leads to an approach of organization design that we call ‘organizational learning’ (Simon, 1991). Organization learning is, according to a wide range of authors afterwards, considered an iterative process of exploration and exploitation that leads to innovation (Garud & Van de Ven, 1992), and more specifically the exploration and exploitation of new business models (Berends, Smits, Reymen, & Podoynitsyna, 2016; Mezger, 2014). In other words, organizational learning is an important prerequisite to innovation and as such a design principle of innovation methodologies.

Kaospilots’ Learning Arches

Knowing that innovation does not happen without learning, it is useful to take a look at how learning happens. One of the more recent approaches to (academic) learning is the so-called ‘Learning Arches Design’ approach, developed and popularized by the Danish firm Kaospilots. According to Simon Kavanagh, “The Learning Arches (LAs) are a method to design transparent, collaborative and experiential learning journeys or processes that maximize engagement, capacity, ambition, ownership, confidence, relevance and most importantly,

dialogue between the learners and hosts, facilitators, instructors or teachers as stakeholders of the learning.” Each learning objective is broken down into smaller objectives that are connected through the arches. Each arch also involves ‘high energy’ stages and ‘low energy’ stages, which follows the natural flow of motivation, looking forward and looking backwards in learning.

When applying the learning arches to the stage-gate framework, we tend not to focus on the outcome but much more on maximizing the learning process itself. The goal of innovation is not optimizing successful innovation as such, but to optimize the amount of individual and group learning in each stage of the process, which in turn, creates a much better performance of ‘organizational learning’ on the long run.

Looking forward to your responses on this line of thinking!