Read full article: University R&D doesn’t create economic growth

Global Strategy Consultancy Firm

Read full article: University R&D doesn’t create economic growth

“Mention the word “innovation” and most people will think of extraordinary inventions created by solitary geniuses,” as mentioned in the first line of Ernst & Young‘s introduction to (one of) their innovation model(s). The article is titled: Innovation for Growth: a spiral approach to business model innovation. A promising introduction: it seems to include (organizational) growth theories, innovation management theory and business model theory. Again, after last year’s successful article on Deloitte’s Fast Growth Track, we’ll take a closer look on this model. Is this model theoretically justified? And if yes – assuming it’s an absolute yes – why does it work and how could it help you?

First of all, let’s take a closer look at one of their general promises; on the one hand the article promises to innovate your business model. Or, as Henry Chesbrough has written it:

“There was a time, not so long ago, when ‘‘innovation’’ meant that companies needed to invest in extensive internal research laboratories, hire the most brilliant people they could find, and then wait patiently for novel products to emerge. Not anymore. The costs of creating, developing, and then shipping these novel products have risen tremendously (think of the cost of developing a new drug, or building a new semiconductor fabrication facility, or launching a new product into a crowded distribution channel). Worse, shortening product lives mean that even great technologies no longer can be relied upon to earn a satisfactory profit before they become commoditized. Today, innovation must include business models, rather than just technology and R&D.”

Source: Chesbrough (20o7): Business Model Innovation: it’s not just about technology anymore

So, the strategic focus of organizations has made a transition from product or service innovation towards business model innovation. That said, it surely doesn’t mean that service or product innovation is of less relevance: it has just shifted from a strategic level to a more tactical level. I got the opportunity ask (well, actually I’m filming, a colleague is asking the questions) Alexander Osterwalder about the place of innovation in the Business Model theory. This is what he said:

So the business model is not directly linked to innovation per se. Osterwalder:

“What it does is, it gives you a language. It’s very tangible, very visual, that will help you to create better conversations and it will make it easier for you to convince people of innovative possibilities.”

Concluding this part: it’s hard to focus on both Business Model Innovation and “Innovation for Growth”, because they are both executed at completely different levels.

Well, so far the analysis of the title page. Let’s take a closer look at their PDF. I will include it here for your convenience:

[gview file=”http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/Growing_beyond_-_Innovation_report_2012/$FILE/Innovation-Report-2012_DIGI.pdf” height=”500px” width=”100%”]

I’ll directly skip to the folowing passage in the text:

“For the most innovative companies today, innovation isn’t a linear process. Rather, it’s a continuous cycle with ups and downs, inputs from different places, repetitions, failures, and many steps back and forth.”

Our guts feeling says that this statement is right. Indeed, it is. Innovation management is a process and many processes are theoretically seen as cycles.The origin of innovation studies lies within the product life cycle, firstly decribed by Lewitt in 1965 and later elaborated on by Perreault, for instance in 2000. It basically consists of four phases: market introduction, market growth, stability and decline. More focused on innovation, Rogers (1995) created a more specified model, ‘the diffusion of innovation and adopter categories.’

These models are singular, while innovation is repeatable. That can be shown by the following figure:

The art of innovation, the process of innovation, is often referred to as innovation management. Innovation Management, or New Business Development, aims to enhance the possibility of technical and commercial success of new products and services (Schilling and Hill, 1998, Brown and Eisenhardt, 1997, Robert, 1994 and Clark and Fujimoto, 1991). The article Fast Track Growth for Innovation shows more indepth information into the different steps of the innovation process.

Typically, each process is cyclic, in order to enhance the room for reflection and dynamical growth. Francis Bacon in 1620 wrote about this explaining that every scientific process should consist of hypothesis – experiment – evaluation. In 1982 Deming developed the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle, which we all have heard of. Cole, in 2002, was the first who explicitly refered to innovation as a cycle: Probe – Test – Evaluate – Learn. Bacon gave his cycle the name ‘inductive approach’ – basically the same as a spiral approach.

So, the circle as round: yes, innovation should be a spiral approach. Below a look on Ernst & Young’s inductive spiral approach:

Wow, that’s something, isn’t it? At least it’s all-inclusive. Let’s take start with the second cycle: “Innovation Process”

Summing up, I’m not very enthousiastic by the spiral approach towards business model innovation of Ernst & Young. It’s mostly a marketing instrument. Though a good one: it includes all expertises that Ernst & Young could probably help you with and is therefore a useful instrument for explaining how they could of help (and not how innovative business models could be (re)developed).

Of course, I will not only analyse the current model, I will also propose a better one. One that takes into account the five steps of the innovative process, but also the recent developments in innovation systems. And I left out all unnecessary information. This is what I get:

Obviously, when ‘walking’ through this innovation process, it’s not necessary to stay at one level and address each step for the same amount of time. It’s more often and iterative process than not, like the following figure shows:

Please, let me know what you think of this analysis. Am I right, or completely wrong?

I would like to end with a quote from Maria Pinelli, Ernst & Youngs Global Vice Chair, which I actually find one of the best quotes I have recently bumped into:

“It is not enough just to be innovative. It is essential to be innovative all the time.”

Recently, I spoke to Deloitte‘s Innovation Concepts Manager Marc Maes and Innovation Consultant Klaas Langeveld about their idea of managing innovation and idea generation within companies. They explained me about their Fast Track strategy and their home-made Innovation Maturity Model. The model intrigued me because of its fairly complete coverage of innovation-related issues and its slim simplicity. It triggered me to grab some literature to find prove of this model. My rationality: if it looks simple and complete, it must be good. And if it’s really good, it must be (partly) supported by earlier findings.

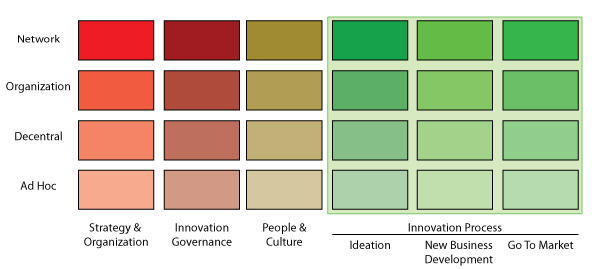

Below, you’ll see the adopted version of Deloitte’s Innovation Maturity Model. The goal of the model is to “score” companies performances on innovation in the model. As Marc and Klaas said, probably in slightly other words, the line should be straight and preferably as high up as possible. Take a look for yourself:

So in the basis the model contains two axes, both unnamed. I’ll try to figure out correct names for them later on. On the vertical axe we’re basicly seeing four forms of doing business. On the horizontal axe we’re seeing management topics, three of which are combined into one: the innovation process. The result of the model would look something like this (I tried to complete them for [edit: anonymized on request], two companies I know fairly well):

Now, it is time to look into some literature and give the two axes name plates. First of all, the vertical axe. The four aspect seem to correlate on “innovation effectiveness”. In innovation literature, when researching the effectiveness of innovation, scholars are often referencing to Organizational Development. Basically, the four above-mentioned steps have a lot in common with Greiner’s model of organizational growth (Greiner, 1972), which still is the most valued model about organization growth. Another perspective would be Rothwell‘s generations of innovation, who looks into adopted innovation models over time and shows the increasing professionalization of innovation management literature. The first three aspects are based on Greiner’s work, the “Network”-factor in Deloitte’s model is more or less based upon Rothwell’s work. Moreover, another traditional model organizational development – and later oftenly used to explain cultural differences – is Quinn & Cameron‘s model for Organizational Growth.

So, to be scientifically correct, I would suggest to use “organizational development” as the dimension of the vertical axis. And, if we would like to stick to just four aspects, then use:

The second axis looks like two groups of aspects that are of interest for innovation managers. But why these? I’m seeing two different groups of aspects:

For the first item, I would suggest to use one of the widely adopted change management models. For instance, the six logical levels interpretated from organizational perspective:

For the second item, which is all about behaviour, Deloitte has suggested three steps that make up the process of innovation. Many scholars have looked into these processes. I’ve gathered some of them:

| (Gopalakrishnan en Damanpour 1997) | (Adams e.a. 2006) | (Goffin en Pfeiffer 1999) | (Verhaeghe en Kfir 2002) | (Rothwell 1992) |

| Inputs | ||||

| Idea Generation | Knowledge management | Creativity | Idea Generation | Idea Generation |

| Project Definition | Human Resources | Technology Acquisition | ||

| Problem Solving | Strategy | Innovation Strategy | Networking | |

| Design and development | Project management | Portfolio Management | Development | Developing, prototyping & manufacturing |

| Marketing and commercialization | Commercialization | Project management | Commercialization | Marketing & Sales |

What we see is that there is no standard for the innovation process. But most of the literature suggests at least three items to be part of every innovation process:

Those items are indeed very coherent with Deloitte’s model for innovation. To my opinion, “knowledge management” should be an integrated part of the innovation process. And then I mean “external knowledge management”, or, if you wish, market research or crowdsourcing. It should be step 0.

All in all, Deloitte’s model would suffice for practical implementation and for companies looking for a way to place their own activities into perspective. Although it needs scientific perfectioning, it is very usable and friendly. What do you think? How is your company performing on the above-mentioned aspects?

Note: Deloitte did not instruct or reward me in any way for writing this article. Above-mentioned perspective is my personal reflection of their model. In fact, we are not only friends, we are also competitors, but that doesn’t mean I could not be interested in their perspective on innovation 😉