Subscribe to our newsletter to receive posts like this weekly.

After our deepdive into the story of Ted Levitt last week, we’ll dive into the extraordinary story of Christopher Freeman (1921 – 2010) this week. By many renowned for his substantial conributions to the academic field of innovation, and as such named a ‘social sciences entrepreneur’ (Fagerberg, Fosaas, Bell and Martin, 2011), Chris Freeman was an expert at the intersection of economics and innovation. His legacy included many ‘firsts’, such as being the first director of SPRU – the Science Policy Research Unit at the University of Sussex -, the first Frascati manual (1962), the first studying ‘technology gaps’ (1960s), the first editor of Research Policy and the author of the first textbook on innovation, ‘The Economics of Industrial Innovation’. His contributions to theory also included works on Industrial Waves and Disruption, National Innovation Systems and The Economics of Change. Freeman had a significant contribution to schumpetarian thinking about disruption.

Background

Christopher Freeman was born in Sheffield in the United Kingdom. He was raised with liberal ideas: his father Arnold worked for the Webb’s whose ‘Fabian Society’ shaped reformist-socialist left-wing views on democracy. His father later on pioneered with ‘Workers’ Educational Association’ and as such also heavily impacted his son’s radical ideas. Christopher Freeman “was educated at the progressive Abbotsholme School in Staffordshire, where he founded a cell of the Young Communist League” (Independent, 2010). He started studying at the London School of Economics (LSE) in 1941, continued in Cambridge to study economics, which he interrupted to join the Royal Military Academy, after which he returned to LSE to graduate in 1948. At LSE he was part of an extraordinary cohort, which included Norman MacKenzie, Claus and Mary Moser and Marion Stern, the mother of Nicholas Stern, an economist and well-known ambassador of taking early action on climate change. Nicholas later said that his passion was largely due to the discussions that he had been part of when his parents, Freeman and other classmates in his early childhood (Stern, 2017). This also forms the main line in Freeman’s career: on the one hand he followed the line of thinking of Schumpeter, popularizing Schumpeter’s – now widely accepted – idea of creative destruction and the fact that there no boundaries to growth, and on the other hand a critical acclaim to capitalism, claiming that a more institutional approach to innovation systems – an approach that is now classified as neo-schumpeterian economics, which takes ingredients from different economic schools such as the austrian school, lausanne school and keynesiasism.

His ideas and early career expertise on innovation policy, led to one of his most famous contributions to the academic world: the notion of innovation systems, and later on also his work on national systems of innovation (Guardian, 2010). He also argued that science plays an important role in establishing industries, much in line with Bernal’s work on the science-based industry and science policies (Fagerberg et al, 2010). As such, he is widely recognized for being ‘an entrepreneur’ in science, developing innovation science as a separate field of study alongside economics, management and entrepreneurship – which led to him being the first director of SPRU – the Science Policy Research Unit at the University of Sussex. As an academic he supervised many scholars, wrote many articles and books and as such had a lasting impact on the science, economics and industry of innovation.

Key Ideas

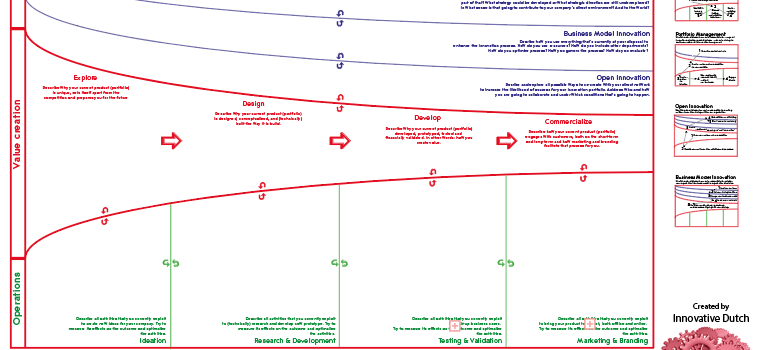

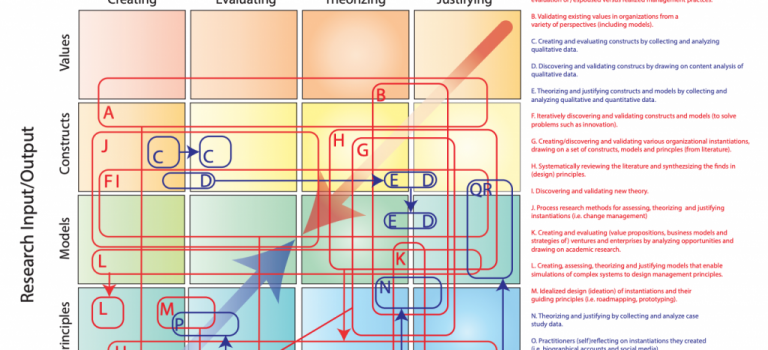

- The Economics of Industrial Innovation: Freeman adopted a dynamic perspective on capitalism, heavily influenced by Marx and Schumpeter. He viewed capitalism as a system characterized by continuous interaction between technological progress, capital accumulation, and social and institutional conditions. Drawing from that, Freeman emphasized the role of technological competition between firms as a driving force behind capitalist development. He focused on understanding the dynamics of technological change within firms and its implications for economic growth and competitiveness. Freeman argued that traditional economic theories often failed to adequately account for the role of research and development (R&D) in driving technological progress and economic development. He highlighted the importance of R&D activities within firms and advocated for policies and management strategies that promote innovation.

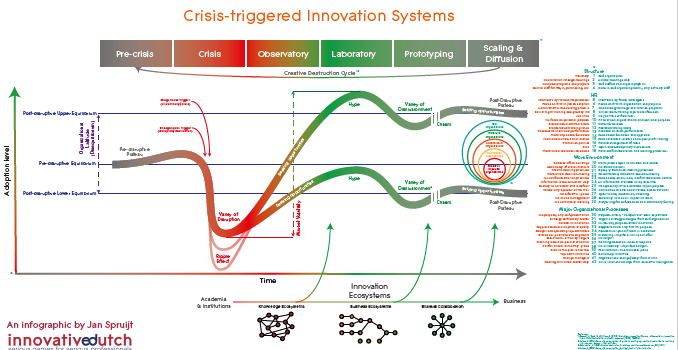

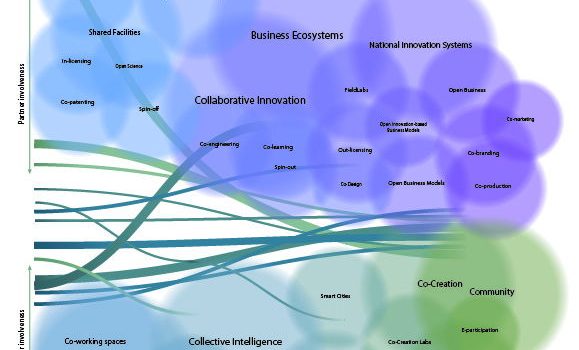

- National Innovation Systems: Freeman, together with i.e. Lundvall, was instrumental in developing the concept of national innovation systems, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of various actors, institutions, and policies within a country that contribute to innovation and economic development. He advocated for a holistic approach to understanding innovation processes, beyond the traditional focus on individual firms or sectors. He emphasized the role of institutions, including government policies, research organizations, universities, and industry associations, in shaping national innovation systems. He argued that effective innovation policies require a deep understanding of the institutional framework within which innovation occurs (Freeman, 1995). In his own words:

“Sectoral systems, regional systems are all very constructive and helpful. (…) You can point to the success of Pakistan in medical instruments or Brazil in boots or shoes or whatever (…) and if you point out the role of innovation in all those micro level studies, that’s very useful. And if you point out certain regions of countries are more innovative, and the north of Italy has contributed more to the growth of the country than Sicily, that’s all very useful. But I don’t think you’ll change the main paradigm of neoclassical economics, I think you have to attack it head on in the centre (…) Most of the people working on innovation systems prefer to work at the micro-level. They are a bit frightened still of the strength of the neoclassical paradigm at the macroeconomic level. But I think that’s where they have to work. You have to have an attack on the central core of macroeconomic theory. It is happening but not happening enough.” (Unpublished interview with Sharif, 2003)

Impact

- Public impact: Freeman highlighted the importance of knowledge diffusion and learning mechanisms within national innovation systems. He emphasized the role of networks, collaborations, and knowledge spillovers in facilitating innovation and technology transfer. Freeman’s work on national innovation systems had significant policy implications. He advocated for policies that promote collaboration between government, industry, and academia, as well as investments in education, research infrastructure, and technology transfer mechanisms. His ideas contributed to the design of innovation policies aimed at enhancing the competitiveness and resilience of national economies (Fagerberg et al, 2011).

- Industrial impact: Freeman emphasized the importance of fostering a culture of innovation within industries. He highlighted the role of research and development (R&D) activities, technological competition, and dynamic interactions between firms in driving innovation. By advocating for policies and management strategies that support innovation, Freeman encouraged industry leaders to prioritize investments in R&D, technology development, and knowledge creation.

- Academic Impact: Under his leadership, SPRU became a global center for innovation research, attracting scholars, policymakers, and industry practitioners from around the world. This collaborative environment facilitated knowledge exchange, interdisciplinary research, and the co-creation of innovative solutions to industry challenges.

Key take-aways

- Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration: Embrace collaborative efforts across disciplines to gain comprehensive insights into innovation dynamics.

- Emphasize a Systems Approach: Consider the historical, economic, and systemic dimensions of innovation to develop a nuanced understanding of its complexities.

- Tap into the Academic Community: Foster an inclusive academic environment that encourages knowledge exchange and inspires new avenues of inquiry in innovation studies.

- Explore Macro-Level Analysis: Delve into macroeconomic perspectives to discern broader implications of innovation on national and regional innovation ecosystems.