Recently, a new article about the “The Golden Circle of Innovation” has been published in the SSRN. It provides an interesting way of combining Simon Sinek’s Golden Circle and some traditional literature on innovation science into the ‘Golden Circle of Innovation’.

Important notice: the full article can be downloaded freely from the SSRN database: The Golden Circle of Innovation: what companies can learn from NGOs when it comes to innovation.

Sinek’s Golden Circle

In his work he explains why everything starts with answering the why-question. And that also means innovation, as he states it: “Knowing your why is not the only way to be successful, but it is the only way to maintain a lasting success and have a greater blend of innovation and flexibility. When a why goes fuzzy, it becomes much more difficult to maintain growth, loyalty and inspiration that helped drive the original success” (Sinek, 2009).

Literature review of Innovation Science

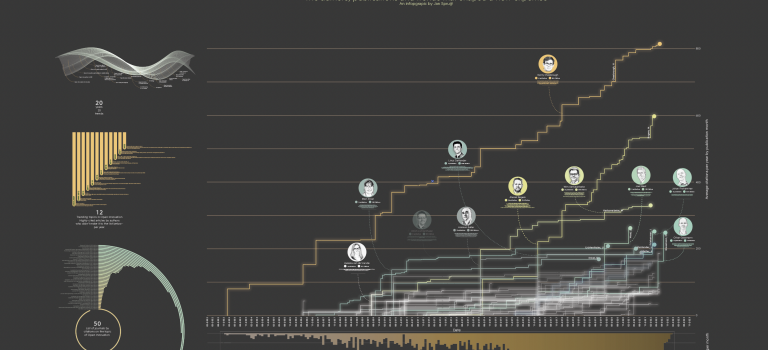

Though not focusing on the why, how and what, Crossan and Apaydin have generated an overview of all relevant theories on innovation, resulting in a framework for innovation, as depicted below.

They mention two ‘dimensions of innovation’, both focusing on innovation itself and they mention several ‘determinants of innovation’, focusing on the way that innovation is accelerated and managed within organizations.

Golden Circle of Innovation

In attempt to combine both models with each other, we created a new framework: the golden circle for innovation.

The why of innovation: grand challenges, trends and mission statements

The why of innovation not only consists of leadership aspects; it also consists of embracing a mission that fulfills a more general need and therefore rectifies the necessity of innovation.

As Einstein once stated “If you always do what you always did, you will always get what you always got”, change is a prime economic driver. “It is practically impossible to do things identically” (Hansen & Wakonen, 1997) which “makes any change an innovation per definition” (Crossan & Apaydin, 2009).

But to what extend? Innovation drives economic growth and economic growth is a necessity because of the grand challenges that this world is facing, such as keeping up with international competition in a globalizing world – which in turn increases the need for higher productivity rates through both product innovation and process innovation (Parisi, Schiantarelli, & Sembenelli, 2006) – and megatrends such as climate change, social problems and the experience economy (Brainport, 2007; Sistermans, Maas, & Soete, 2005).

So how are great leaders capable of embracing this necessity for innovation and embed it into their vision for the company? Dyer, Christensen and Gregerson (Dyer, Gregersen, & Christensen, 2009) undertook “a six-year study into the origins of creative – and often disruptive – business strategies in innovative companies”. They found evidence that these leaders are visionary and much more facilitating the innovation process than actually coming up with innovations themselves. They are drivers of the process. Their study results in five ‘discovery skills’ that these inspirational leaders do 50% better than their non-creative counterparts:

- Associating

- Questioning

- Observing

- Experimenting

- Networking

Concluding this paragraph, we can state that an effective answer the why of innovation consists of both a motivational mission statement that embraces one or more grand challenges that is functioning as the beating heart of the organization and inspirational leaders that are effective in the five before-mentioned discovery skills.

The how of innovation: innovation history, management and processes

Innovation has a basis in the product life cycle. Literature on this topic goes back centuries, but was first scientifically mentioned by Levitt (Levitt, 1965). In several revising studies, Perreault has elaborated on this model (Perreault, McCarthy, Parkinson, & Stewart, 2000). The model consists of the four phases a product or service are subject to: market introduction, market growth, market stability and decline. From an innovation perspective, Rogers has created a model that characterized final consumers to the extend in which they adopt to new technologies: The Diffusion of Innovation and Adopter Categories (Rogers, 2002).

In recent decades, a lot of research has been performed into innovation processes and the steps that regularly seem to reoccur in these processes. Literature reviews show there is little consensus about the number of phases and types of phases that should be part of a regular innovation cycle (Adams, Bessant, & Phelps, 2006; Gopalakrishnan & Damanpour, 1997).

De Brentani and Reid further elaborate on this model (Reid & De Brentani, 2004). They state that incremental, structured innovations are mostly the result of explicit and structured innovation processes and organizational processes. On the other hand, unstructured innovation processes (especially in the first one or two phases) often lead to disruptive or radical innovations. This is also called the ‘fuzzy front end’ of innovation (Brentani & Reid, 2012). Structure and organisation in later phases of innovation processes is always a pro for the success rate of innovation. In what way does the fuzzy front end of innovation differ with structured innovation?

- There is continuous unstructured problem identification and unstructured opportunity recognition, whereas more structured innovation processes mostly use problem structuring and opportunity structuring and the early phases of the process (Hauser, Urban, & Weinberg, 1993; Leifer, O’Connor, & Rice, 2001).

- Information collection and information exploration is generally outside-in oriented, whereas these steps are often inside-out oriented in structured processes.

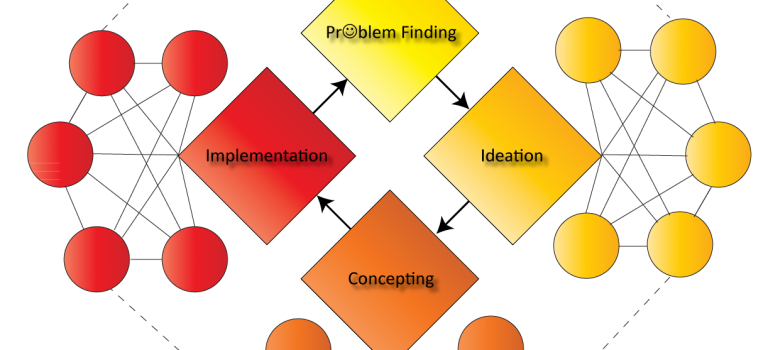

This theory is further elaborated on by Mance, Murdock and Puccio, who have generated the following model (Puccio, Mance, & Murdock, 2010).

At this point, we have tried to deduce a model that comprises all before-mentioned models and consequently consists of four phases that each have the form of diverging-converging, but also as a total has to form of diverging-converging.

Similar like organizations growth models, the area of innovation management has been undergoing several improvements over the years. Rothwell has stated that market changes have contributed to these improvements and he distinguishes five different generations of innovation:

- 1st generation: technology push

- 2nd generation: market pull

- 3rd generation: coupled innovation

- 4th generation: integrated innovation

- 5th generation: open innovation

Concluding this paragraph, we can state that as part of the how of innovation the processes should be oriented at following a pragmatic approach – such as problem finding, ideation, concepting and implementation – and should consist of both a structured inside-out approach and a more chaotic outside-in approach and that the management should be oriented at successful implementation and embedding new approaches to innovation management, such as open innovation.

The what of innovation: innovation as a process and as an outcome

There are various definitions of innovation. In an earlier article, we have used the following, fairly narrow defined, definition of Schilling: “Innovation is the act of introducing a new device, method or material for application to commercial or practical objectives” (M.A. Schilling, 2005; Spruijt, 2012). Crossan & Apaydin recently published a literature review on innovation literature, stating: “An unrestricted search of academic publications using the keyword innovation produces tens of thousands of articles, yet reviews and meta-analyses are rare and narrowly focused, either around the level of analysis (individual, group, firm, industry, consumer group, region, and nation) or the type of innovation (product, process, and business model)” (Crossan & Apaydin, 2009). To be specific, a current search on the keyword “innovation” results in 2.5 million articles on Google Scholar and thousands of articles using the keyword combination “definition of innovation”. Clearly, there isn’t a specific definition that is correct and many perspectives should be taken into account when defining innovation.

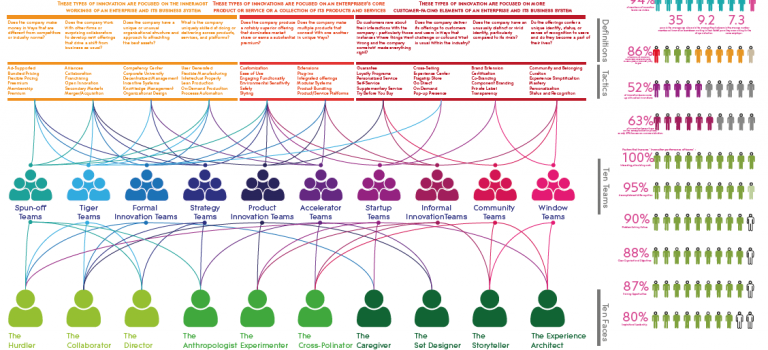

Crossan and Apaydin (2009) have identified different forms of innovation and grouped them around certain dimensions, some of them related to innovation as a process, some of them to innovation as an outcome. These dimensions are:

Innovation as a process:

- drivers of innovation

- levels of innovation

- direction of innovation

- source of innovation

- locus of innovation

Innovation as an outcome:

- forms of innovation

- magnitude of innovation

- referent of innovation

- type of innovation

Golden Circle of Innovation

This leads to a more detailed model of the one we presented earlier:

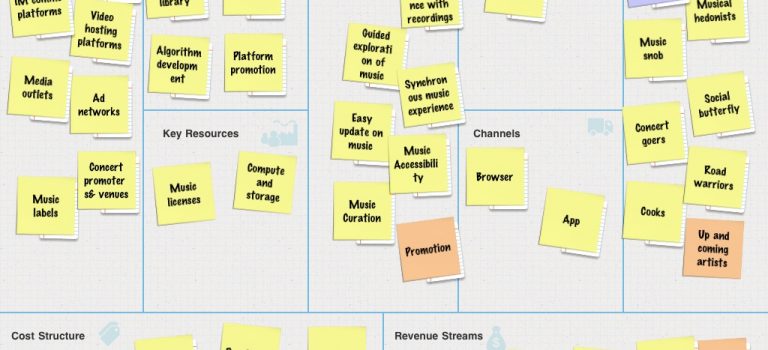

Example case of NGOs

During the studies we followed the Liliane Foundation in an innovation project aiming to create more awareness amongst high school students about the problems in third world countries. They collaborated with a group of students from Avans University in order to identify the problems. These students are high school dropouts and were able to address the problem very efficiently. In a next step, the Liliane Foundation gathered a group of high school teachers to further develop ideas and alternative programs for awareness. In a third step, they collaborated with high school executives and university executives in order to create a platform for the implementation of the alternative programs and to find financial contribution. In the last phase, the implementation, they collaborated with all parties and included some external partners, mostly sponsors, in the roll out. The whole project was successfully launched within a year.

So what did they do? They used their why to find partners that were willing to help them executing the how. They found a way of ‘open innovation’ that is rarely seen in the corporate world, as depicted in the following figure.

Important notice: the full article can be downloaded freely from the SSRN database: The Golden Circle of Innovation: what companies can learn from NGOs when it comes to innovation.