Every week, this section contains newly published scientific articles in the field of innovation & entrepreneurship. This section contains the #EditorsChoice and a list of articles grouped into #MustReads, #ShouldReads and #CouldReads. Subscribe to our newsletter to receive these in your inbox.

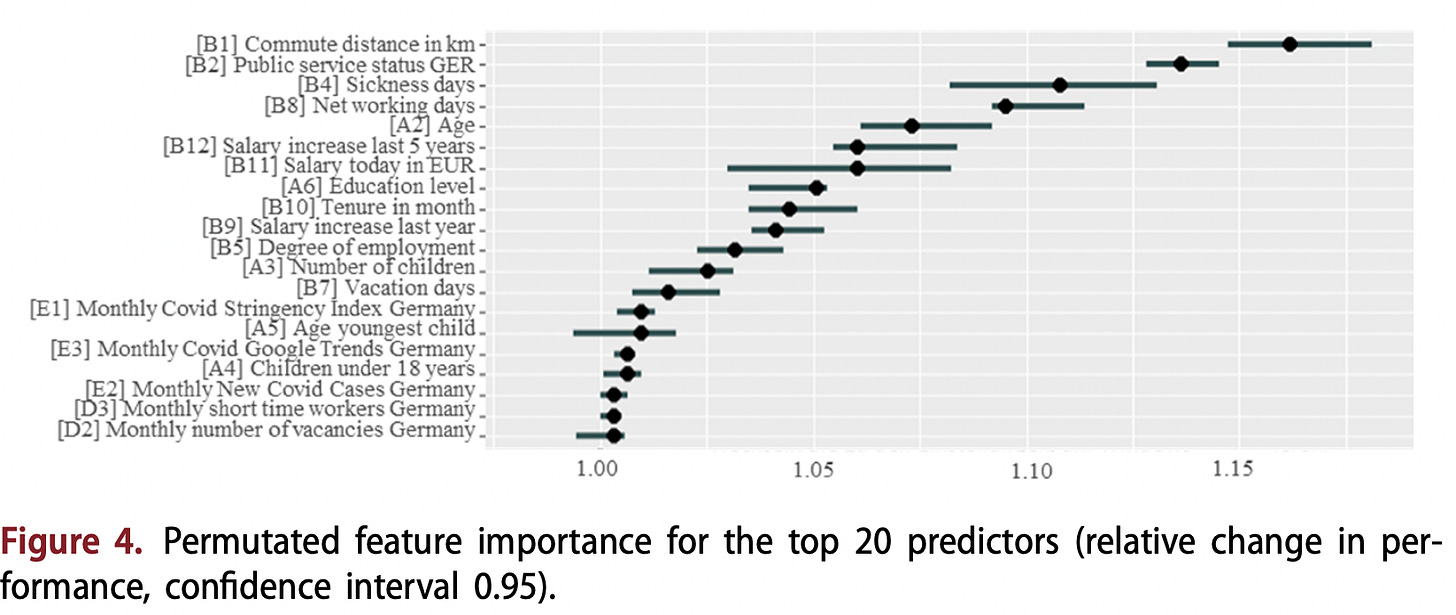

- #EditorsChoice: Machine learning with real-world HR data: mitigating the trade-off between predictive performance and transparency (Heidemann, Hülter & Tekieli, 2024) Researchers have decoded the enigma of Machine Learning (ML) in Human Resource Management (HRM). Their groundbreaking study reveals a crucial trade-off: as ML algorithms get smarter, they become less transparent. But fear not! Enter post-hoc explanatory methods, shedding light on ML’s inner workings without sacrificing accuracy. What does this mean? HR teams can now make informed decisions, harnessing the power of ML while maintaining clarity. From reducing turnover rates to empowering public sector organizations, the possibilities are endless in this new era of HRM.

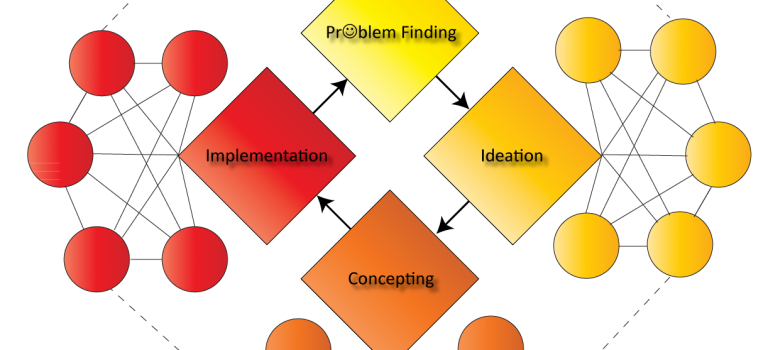

- #MustRead: Complex Problem Solving as a Source of Competitive Advantage (Veríssimo et al, 2024): The study emphasizes the increasing importance of problem-solving skills in today’s complex business environment. Solving complex problems is identified as a crucial skill that can enhance organizational success and competitiveness. Understanding the value of problem-solving and incorporating it into organizational strategy is essential for achieving sustainable competitive advantage in today’s dynamic business landscape.

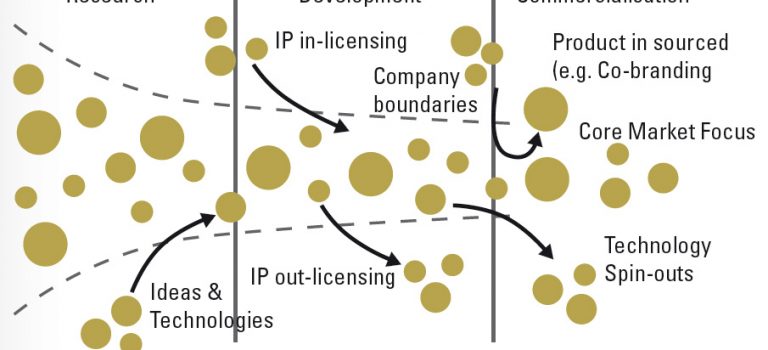

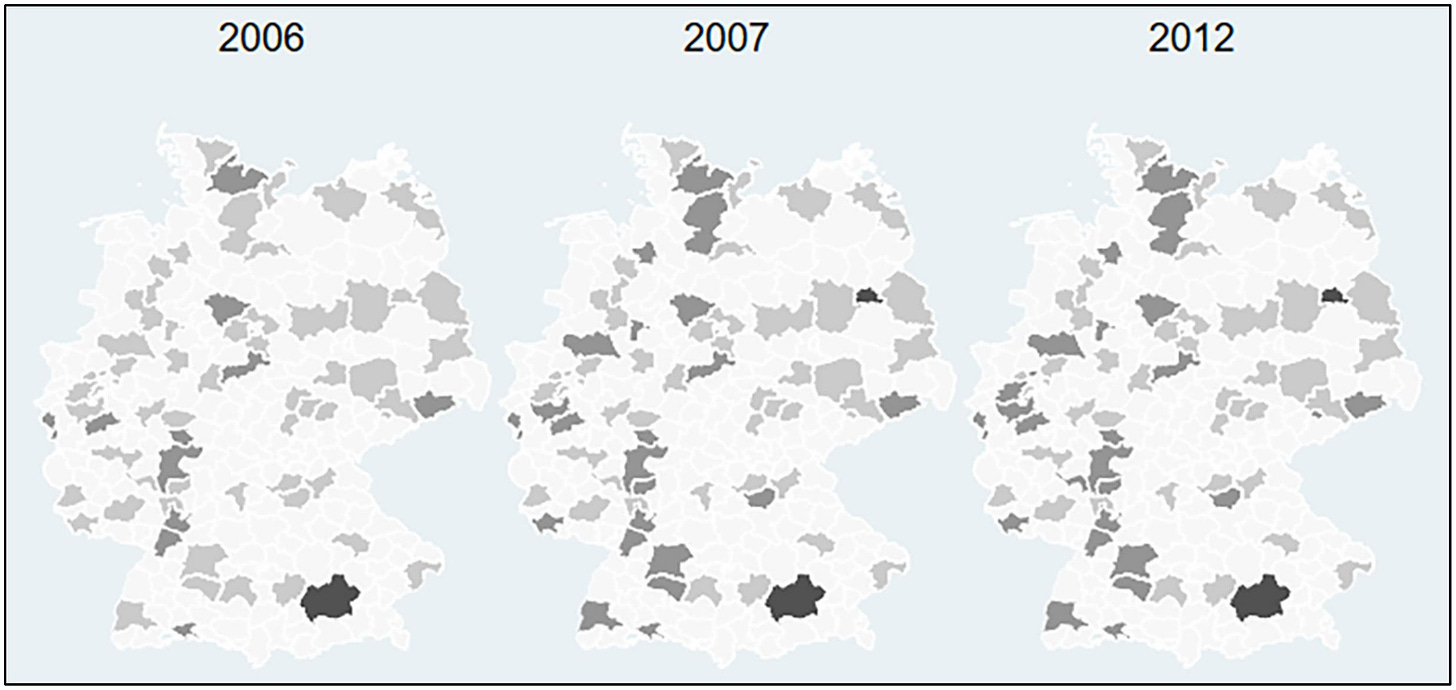

- #MustRead: Heterogeneous university funding programs and regional firm innovation: An empirical analysis of the German Excellence Initiative (Krieger, 2024) In a revealing study, researchers unveil the hidden power of university funding in driving regional innovation. Their findings reveal that targeted investment in Excellence Clusters turbocharges firms’ ability to innovate, particularly in regions with a robust cluster presence. However, the impact of Graduate Schools or University Strategies remains underwhelming. This discovery underscores the pivotal role of strategic funding in shaping the innovation landscape, sparking vital discussions on optimizing investment strategies to supercharge regional growth.

- #MustRead: Neuroentrepreneurship: state of the art and future lines of work (Juarez-Varón, Zuluaga & Recuerda, 2024) Neuroentrepreneurship, a field at the intersection of neuroscience and entrepreneurship, has gained traction since 2009, illuminating how brain function influences business decisions. Despite a growing body of literature, a unified understanding of the field remains elusive. This paper addresses this gap by examining key themes in neuroentrepreneurship literature and refining definitions to provide clarity. Understanding the neural mechanisms behind entrepreneurial behavior offers practical insights for decision-making and opportunity recognition. By leveraging biometric techniques like EEG and GSR, entrepreneurs can gain a deeper understanding of risk perception and response. This review not only consolidates existing knowledge but also provides a framework for future research and practical applications in enhancing entrepreneurial decision-making processes.

- #ShouldRead: Middle Managers’ Relational Dynamics in the Context of Acquisitions: Balancing Strategic Interdependence and Organizational Autonomy (Birollo, Rouleau & Wolf, 2024): Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) pose a challenge in balancing the need for strategic interdependence with the preservation of organizational autonomy. Middle managers (MMs) are identified as key players in this balancing act. Intersubjectivity refers to the mutual understanding and shared meaning that arises between individuals through interaction, enabling effective communication and collaboration. In mergers, intersubjectivity is crucial as it facilitates middle managers’ ability to navigate complex integration tasks by considering the perspectives and goals of both acquiring and acquired organizations, fostering smoother transitions and alignment of objectives. Similarly, in innovation, intersubjectivity fosters a collaborative environment where diverse perspectives and insights can converge, leading to the co-creation of novel solutions and the maximization of creative potential within teams and across organizational boundaries.Figure 2: A process model of actionable intersubjectivity as a crucial ability for balancing strategic interdependance and organizational autonomy (Birollo et al, 2024)

- #ShouldRead: Age and entrepreneurship: Mapping the scientific coverage and future research directions (Syed et al, 2024) Research interest in understanding the relationship between age and entrepreneurship has surged in recent years, driven by the recognition of age as a significant factor influencing entrepreneurial behavior and career decisions. Various studies have explored the motivational factors shaping self-employment decisions, revealing age’s nuanced impact on entrepreneurial intentions and actions. While younger individuals may exhibit greater enthusiasm for entrepreneurship due to their ambitious nature and future income potential, older individuals leverage their extensive experience and social capital to navigate entrepreneurial ventures successfully. However, age-related preferences, influenced by factors such as cultural views and opportunity costs, also play a role in shaping entrepreneurial pursuits.

- #ShouldRead: The Double-Edged Sword of Exemplar Similarity (Majzoubi et al, 2024) Ever wondered how your firm’s image relative to industry leaders affects investor perception? New research spills the beans! Aligning with category exemplars boosts your firm’s visibility and initial screening success. But beware: it also triggers comparisons that might not always work in your favor. The key? Understanding your industry’s landscape and positioning strategically. Dive into the study for practical insights to finesse your firm’s approach and ace those investor evaluations!

- #CouldRead: Evaluating the impact of individual and country-level institutional factors on subjective well-being among entrepreneurs (Gashi et al, 2024): This study explores the relationship between subjective well-being (SWB) and entrepreneurship. Stimuli of well-being are: fostering political stability, reducing bureaucratic hurdles, and promoting economic prosperity to support entrepreneurial ventures and enhance overall satisfaction. The study also offers practical suggestions for entrepreneurs to improve their well-being, such as self-care, meaningful engagement, building strong support networks, prioritizing health, and finding purpose in their work.

- #CouldRead: Financial stress and quit intention: the mediating role of entrepreneurs’ affective commitment (Kleine, Schmitt & Wisse, 2024) This paper delves into how financial stress impacts entrepreneurs’ desire to quit their businesses, focusing on the emotional connection entrepreneurs have with their ventures. The findings suggest that when entrepreneurs face financial stress, they’re more likely to consider quitting, especially when their emotional attachment to the business decreases. Essentially, the stronger the emotional bond with their venture, the more likely they are to persist through tough times. These insights can guide consultants and decision-makers to support entrepreneurs effectively. For instance, if a business has potential, efforts to boost the entrepreneur’s emotional commitment could increase motivation to overcome challenges. Conversely, if closure seems inevitable, strategies to help entrepreneurs emotionally detach from the business may prevent further losses. Overall, understanding and addressing entrepreneurs’ emotional ties to their ventures can inform practical strategies to navigate financial difficulties and plan for the future effectively.